Body Language of Symbolic Stripping or Removing Clothing

Cue: Symbolic Stripping or Removing Clothing.

Cue: Symbolic Stripping or Removing Clothing.

Synonym(s): Removing Clothing.

Description: Includes loosening ties, removing jackets or over-shirts, rolling up the sleeves, undoing buttons and so forth.

In One Sentence: Removing clothing signals either a desire to get more comfortable, a desire to get down to business, or an attempt to seduce.

How To Use it: Remove clothing when you want others to see that you are ready for action. This is potent in business where removing a jacket signals that it’s time to get some real work done. While negotiating, the same signal is sent – that we’re getting serious about the task at hand. Removing clothing can also be used to tell others that they need to relax and settle in for the long haul. When bargaining, this tells them that they should present the most attractive offer first, or risk a long negotiation.

Removing clothing such as a jacket upon arrive at a persons house tells them that one isn’t ready to leave and that one feels welcome. Thus, removing clothing is paid as a compliment.

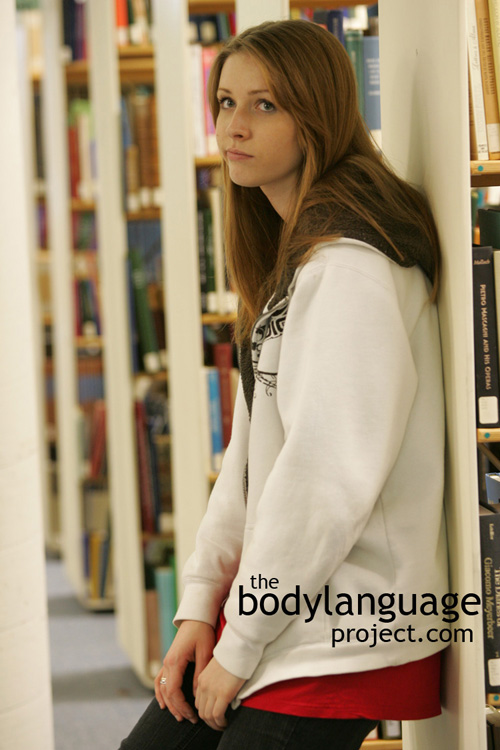

In dating, removing outer clothing is a similar comfort indicator. Therefore, women can tell their dates that they are “warming up” to them and feel relaxed enough to expose more of their body. The more skin that is exposed; the stronger the sexual implication. Women can boost the signal’s strength and arouse men further by removing clothing while making direct eye contact. This serves to indicate metaphorical stripping as eye contact anchors the signal to a specific person – “I’m undressing for you.”

Context: a) General b) Business c) Dating.

Verbal Translation: a) “I’m getting more comfortable because I feel at ease and relaxed so I’m removing some of my clothing” or “I’m hot so I’m removing some of my clothing.” b) “It’s time to get down to business, let’s take our coats off and rolls up our sleeves and get the job done.” c) “I’m interested in you sexually, so I’m going to take off my overcoat and expose my skin to try to get you worked up.”

Variant: See Rolled Up Sleeves.

Cue In Action: a) She made her way into her friend’s house. First she removed her shoes and jacket. By the end of the night she was minus her hooded shirt and socks. She really made herself at home. b) The boss was serious. He removed his jacket, put his hands palm down on the desk and spoke firmly, “There would be no more goofing around on company time.” c) She excused herself to the washroom. When she returned, her blouse was unbuttoned revealing cleavage. She intended to peak his sexual curiousity.

Meaning and/or Motivation: The nonverbal message that removing clothing entails is mixed and highly dependent on the context.

Men will almost always remove clothing to get more comfortable, but may also remove a shirt to arouse. The reaction that removing a shirt has when a man reveals a muscular physique is no different then when a woman reveals her sexual assets by removing clothing.

Removing clothing can deliver a sexual message in a romantic situation, getting down to business at work, or comfort when done amongst friends. In a dating context, removing a heavy shirt or jacket to be more comfortable, or loosening buttons from a shirt, or even removing shoes or dangling the shoes from the toe, all show comfort at worst, and interest at best.

This cue therefore, must be read in context with adjoining cues.

Cue Cluster: a) and b) In a general and business context, removing clothing will be almost entirely dependent on the context but can also be confused with c) dating. Therefore, watch for additional sexual cues of interest to determine if the cue is sexual in nature. In women, one might watch for strong eye contact, head lowered or tilted to the side, batting eyes, wrist and neck exposure, touching, lip licking, proximity and so forth. Men might pull a shirt off around the pool and pull their shoulders back to showcase them, hold their chin up and hold strong eye contact. They may smirk.

Body Language Category: Adaptors, Amplifier, Comfort body language, Courtship display, Indicators of sexual interest (IOsI), Relaxed body language.

Resources:

Anat Rafaeli; Jane Dutton; Celia V Harquail; Stephanie Mackie-Lewis. Navigating by attire: The use of dress by female administrative employees. Academy of management journal. 1997. 40 (1): 9-45.

Adam, Hajo and Adam D. Galinsky. Enclothed Cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012. 48 (4): 918–925. DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.008 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103112000200

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/wearing-white-coat-boosts-performance-enclothed-cognition/

Abbey, A., Cozzarelli, K., McLaughlin, K., & Harnish, R. (1987). The effects of clothing and dyad sex composition on perceptions of sexual intent: Do women and men evaluate these cues differently? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 17: 108-126.

Bettis, Pamela J. ; Adams, Natalie Guice. Short Skirts and Breast Juts: Cheerleading, Eroticism and Schools. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning. 2006. 6(2): 121-133.

Barber, Nigel. Women’s dress fashions as a function of reproductive strategy. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 1999. 40(5-6): 459(1).

Beiner, Theresa M. Sexy dressing revisited: does target dress play a part in sexual harassment cases? Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy. 2007 14(1): 125(28).

Buckley, Hilda Mayer ; Roach, Mary Ellen. Clothing as a Nonverbal Communicator of Social and Political Attitudes. Home Economics Research Journal. 1974 3(2): 94-102.

Back, Mitja D. ; Schmukle, Stefan C. ; Egloff, Boris King, Laura (editor). Why Are Narcissists so Charming at First Sight? Decoding the Narcissism–Popularity Link at Zero Acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010. 98(1): 132-145.

Cari D. Goetz; Judith A. Easton; David M.G. Lewis; David M. Buss. Sexual Exploitability: Observable Cues And Their Link To Sexual Attraction. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2012; 33: 417-426.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/victim-blaming-or-useful-information-in-preventing-rape-and-sexual-exploitation/

Clark, A. Attracting Interest: Dynamic Displays of Proceptivity Increase the Attractiveness of Men and Women. Evolutionary Psychology. 2008., 6(4), 563-574.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/risky-versus-proceptive-nonverbal-sexual-cues/

Chowdhary, U. 1988. Instructor’s attire as a biasing factor in students’ ratings of an instructor. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal 6 (2): 17-22.

Cahoon, DD; Edmonds, EM 1989. Male-Female Estimates Of Opposite-Sex 1st Impressions Concerning Females Clothing Styles Bulletin of the psychonomic society. 27(3): 280-281.

Chowdhary, U. 1988. Instructor’s attire as a biasing factor in students’ ratings of an instructor. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal 6 (2): 17-22.

Cahoon, DD; Edmonds, EM 1989. Male-Female Estimates Of Opposite-Sex 1st Impressions Concerning Females Clothing Styles Bulletin of the psychonomic society. 27(3): 280-281.

Cassidy, Linda ; Hurrell, Rose Marie. The influence of victim’s attire on adolescents’ judgments of date rape. Adolescence. 1995 30(118): 319(5).

Dosmukhambetova, D., and Manstead, A. Strategic Reactions to Unfaithfulness: Female Self-Presentation in the Context of Mate Attraction is Link to Uncertainty of Paternity. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2011. 32, 106-107.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/sexy-clothing-source-power-women/

Durante, Kristina M ; Li, Norman P ; Haselton, Martie G. Changes in women’s choice of dress across the ovulatory cycle: naturalistic and laboratory task-based evidence. Personality & social psychology bulletin. 2008 34(11): 1451-60.

Edmonds, Ed M.; Cahoon, Delwin D.; Hudson, Elizabeth 1992. Male-female estimates of feminine assertiveness related to females’ clothing styles. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 30(2): 43-144.

Edmonds, Ed M.; Cahoon, Delwin D.; Hudson, Elizabeth 1992. Male-female estimates of feminine assertiveness related to females’ clothing styles. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 30(2): 43-144.

Forsythe, S., M. F. Drake, and C. E. Cox. 1985. Influence of applicant’s dress on interviewer’s selection decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology 70 (2): 374-378

Forsythe, S. M., M. F. Drake, and C. A. Cox Jr. 1984. Dress as an influence on the perceptions of management characteristics in women. Home Economics Research Journal 13 (2): 112-121

Forsythe, S. M. 1990. Effect of applicant’s clothing on interviewer’s decision to hire.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology 20 (19, 1): 1579-1595.

Guéguen, Nicolas. The Effect Of Women’s Suggestive Clothing On Men’s Behavior And Judgment: A Field Study. Psychological Reports. 2011. 109; 2: 635-638.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/sexy-clothing-source-power-women/

Farris, Coreen ; Viken, Richard J. ; Treat, Teresa A. Perceived association between diagnostic and non-diagnostic cues of women’s sexual interest: General Recognition Theory predictors of risk for sexual coercion. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2010. 54(1): 137-149.

Gurung, R. A. R. and C. J. Chrouser. 2007. Predicting objectification: do provocative clothing and observer characteristics matter? Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 57 (1-2): 91-99.

Goetz, Cari D.; Judith A. Easton; Cindy M. Meston. The Allure of Vulnerability: Advertising Cues to Exploitability as a Signal of Sexual Accessibility. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013. 62: 121-25.http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/allure-sexual-vulnerability-move/

Grammer, Karl, LeeAnn Renninger and Bettina Fischer. Disco Clothing, Female Sexual Motivation, and Relationship Status: Is She Dressed to Impress? The Journal of Sex Research. 2004. 41(1): 66-74.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/is-she-dressed-for-success-how-women-adorn-during-courtship/

Glick, Peter ; Larsen, Sadie ; Johnson, Cathryn Branstiter, Heather. Evaluations of Sexy Women in Low-And High-Status Jobs. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005. 29(4): 389-395.

Graff, Kaitlin ; Murnen, Sarah ; Smolak, Linda. Too Sexualized to be Taken Seriously? Perceptions of a Girl in Childlike vs. Sexualizing Clothing. Sex Roles. 2012. 66(11): 764-775.

Garot, Robert ; Katz, Jack. Provocative Looks: Gang Appearance and Dress Codes in an Inner-City Alternative School. Ethnography, 2003, Vol.4(3), pp.421-454

Greenless, Iain ; Buscombe, Richard ; Thelwell, Richard ; Holder, Tim ; Rimmer, Matthew. Impact of opponents’ clothing and body language on impression formation and outcome expectations. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2005 27(1): 39-52.

Greenlees, Iain ; Bradley, Andrew ; Holder, Tim ; Thelwell, Richard. The impact of opponents’ non-verbal behaviour on the first impressions and outcome expectations of table-tennis players. Psychology of Sport & Exercise. 2005 6(1): 103-115

Hernandez, Jillian. “Miss, you look like a Bratz Doll”: on chonga girls and sexual-aesthetic excess.(Report). NWSA Journal. 2009 21(3): 63(28).

Haselton, M. G., M. Mortezaie, E. G. Pillsworth, A. Bleske-rechek, and D. A. Frederick. 2007. Ovulatory shifts in human female ornamentation: near ovulation, women dress to impress. Hormones and Behavior. 51(1): 40-45.

Hald, G. M., & Høgh-Olesen, H. Receptivity to Sexual Invitations from Strangers of the Opposite Gender. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2010. 31, 453-458.

Johnson, Richard R. and Jasmine L. Aaron. Adults’ Beliefs Regarding Nonverbal Cues Predictive of Violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2013. 40 (8): 881-894. DOI: 10.1177/0093854813475347.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/wanna-fight-nonverbal-cues-believed-indicate-violence

Karagiorgakis, Aris and Danielle Malone. The Effect of Clothing and Method of Payment on Tipping in a Bar Setting. North American Journal of Psychology. 2014. 16(3): 441-452.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/skimpy-clothing-lead-larger-tips-boost-tips-using-nonverbal-communication/

Keiierman, Joan M. and James D. Laird. The Effect of Appearance on Self Perception. Journal of Personality. 1982; 50: 3. http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/eye-glasses-body-language-brief-summary/

Koukounas, Eric ; Letch, Nicolem. Psychological Correlates of Perception of Sexual Intent in Women. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2001. 141(4): 443-456.

Karl, Katherine A. ; Hall, Leda Mcintyre ; Peluchette, Joy V. City employee perceptions of the impact of dress and appearance: you are what you wear. Public Personnel Management. 2013 42(3): 452(19).

Lõhmus, Mare, L.; Fredrik Sundström and Mats Björklund. Dress for Success: Human Facial Expressions are Important Signals of Emotions. Annales Zoologici Fennici. 2009. 46: 75-80.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/ugly-clothing-also-makes-face-ugly

Lynch, A. Expanding the Definition of Provocative Dress: An Examination of Female Flashing Behavior on a College Campus. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal. 2007. 25(2): 184-201.

Morris, T. L., J. Gorham, S. H. Cohen, and D. Huffman. 1996. Fashion in the classroom: effects of attire on student perceptions of instructors in college classes. Communication Education 45(2): 135.

Moore, M. M. and D. L. Butler. 1989. Predictive aspects of nonverbal courtship behavior in women. Semiotica 76(3/4): 205-215.

Moore, M. M. 2001. Flirting. In C. G. Waugh (Ed.) Let’s talk: A cognitive skills approach to interpersonal communication. Newark, Kendall-Hunt.

Moore, M. M. 1985. Nonverbal courtship patterns in women: context and consequences. Ethology and Sociobiology 64: 237-247.

Mahmuda, Yusr and Viren Swami. The Influence of the Hijab (Islamic Head-Cover) on Perceptions of Women’s Attractiveness and Intelligence. Body Image. 2010. 7: 90-93.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/hijabs-hot-nonverbal-effect-hijab-attractiveness-intelligence-ratings/

Mcginley, Ann C. Babes and beefcake: exclusive hiring arrangements and sexy dress codes. Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy. 2007 14(1): 257(27).

Markey, Patrick ; Markey, Charlotte. Changes in women’s interpersonal styles across the menstrual cycle. Journal of Research in Personality. 2011. 45(5): 493-499.

Parsons, Charles K. ; Liden, Robert C. Guion, Robert (editor). Interviewer perceptions of applicant qualifications: A multivariate field study of demographic characteristics and nonverbal cues. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1984 69(4): 557-568.

Peluchette, J. V., K. Karl, and K. Rust. 2006. Dressing to impress: beliefs and attitudes regarding workplace attire. Journal of Business and Psychology 21(1): 45-63.

Parks, Kathleen ; Scheidt, Douglas. Male Bar Drinkers’ Perspective on Female Bar Drinkers. Sex Roles, 2000, Vol.43(11), pp.927-941.

Regan A. R. Gurung & Carly J. Chrouser. Predicting Objectification: Do Provocative Clothing and Observer Characteristics Matter? Sex Roles, 2007; 57: 91–99.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/dont-want-to-be-objectified-then-dont-wear-sexy-clothing-says-research/

Richards, Lynne ; Mcalister, Laurie. Female Submissiveness, Nonverbal Behavior, and Body Boundary Definition. The Journal of Psychology. 1994 128(4): 419-424.

Rehman, Shakaib U. ; Nietert, Paul J. ; Cope, Dennis W. ; Kilpatrick, Anne Osborne. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients

The American Journal of Medicine. 2005 118(11): 1279-1286.

Starr, Christine ; Ferguson, Gail. Sexy Dolls, Sexy Grade-Schoolers? Media & Maternal Influences on Young Girls’ Self-Sexualization. Sex Roles. 2012. 67(7): 463-476.

Synovitz, Lindab. ; Byrne, T. Jean. Antecedents of Sexual Victimization: Factors Discriminating Victims From Nonvictims. Journal of American College Health. 1998. 46(4): 151-158.

Sandlund, Chris. Put Some Clothes On! (employee dress rules). Entrepreneur. 2001 29(8): 70.

Vazire, Simine; Laura P. Naumann; Peter J. Rentfrow and Samuel D. Gosling. Portrait of a Narcissist: Manifestations of Narcissism in Physical Appearance. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008. 42: 1439-1447.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/narcissist-written-read-body-language-narcissist/