Body Language of The Stare, Evil Eye or Unblinking Eye

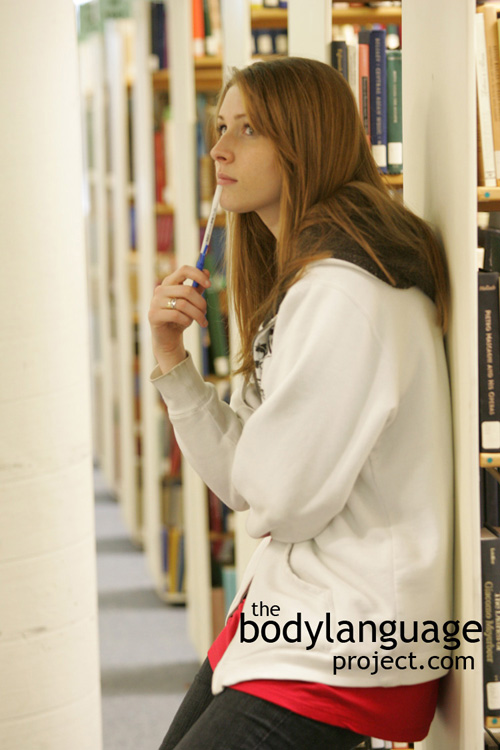

Cue: Staring or The Evil Eye.

Cue: Staring or The Evil Eye.

Synonym(s): Stink Eye, Dead Man Gaze, Unflinching Stare, Stare, Gaze Fixation, Unblinking Eye, Eye Threat, Eye Darts, Prolonged Eye Contact, Unwavering Gaze, Power Star (the), Unflinching Stare.

Description: These are unblinking staring eyes filled with contempt. The evil eye is an offensive eye pattern where the eyes remain unblinking and threatening or leer at another person for an uncomfortable length of time. Regular gaze happens when the eyes travel around the face and body of someone we care about. Staring, on the other hand, is unmoving. The eyes are piercing and intense and seem to want to penetrate the eyes of another. An aggressive stare is even more intense and happens by narrowing the eyelids creating a deep focus.

In One Sentence: Staring for prolonged period of time is in effort to reduce a person to the status of an object.

How To Use it: Use staring when one wants to intimidate others. Staring harshly during aggression can belittle and degrade. When it is done in a sexual context, staring can diminish a person to a lesser status as an object.

In dating, men might view staring as being a compliment, however, if the feelings are not mutual, women will feel violated due to their perceived powerlessness. Therefore, men should only use staring (see Gazing adoringly) to support an existing emotional connection.

Use staring when one is prepared for the negative outcome. As a signal of dominance, the cue is unmistakable.

Context: a) General b) Dating.

Verbal Translation: “I’m using inappropriately long and violating eye contact in order to pierce through your exterior in order to threaten and intimidate.”

Variant: See Gazing Adoringly for a more welcome version of The Stare. Also see Eye Avoidance.

Cue In Action: a) Mark was in a stupor and accidentally bumped into a girl. He didn’t know it but she was the girlfriend of the muscle-bound man who immediately threw eye darts in his direction, unflinching and steady. Mark quickly averted his eyes because he knew it wasn’t a fight for him. Despite looking away, he still felt the piercing stare against his body

b) A particularly attractive girl made her way through a crowd, you could see men turn their heads, but one man made the mistake of looking for too long as he followed her through the crowd. She didn’t like the look of him and stared right back. He smiled, but she didn’t reciprocate; only a deadpan face looked back. He quickly averted his eyes.

Meaning and/or Motivation: Staring is built on the assumption that eyes can damage from prolonged looking. It is as if the eyes are able to assault when eye contact is done for too long and without permission. This violates the “moral looking time”, or the unwritten code of conduct we all obey regarding proper eye contact. As a result, it produces negative feelings in others.

a) In most animal species unwavering gaze is used to display dominance and aggression. However, this is only so when it happens between members of the same species. When it happens across species it indicates that a prey has been centered out and the stalk has begun.

Research shows us that a steady stare of more than ten seconds creates anxiety and discomfort especially in subordinates making it a dominant signal especially when this includes direct eye-to-eye contact. When done by two equally dominant individuals it can lead to feelings of aggression and in extreme cases, even produce physical altercations.

b) Eye assault happens when men appear to undress women. In turn, women might appear to give “dirty looks.” We call this “eyeball assault.” Assault is a matter of length and type. Lingering stares of unbroken eye contact is the high of eyeball assault. Eyeball assault, therefore, violates the “moral looking time.” This is an unofficial, but salient length of time by which eye contact (to the body or eyes directly) is permitted and accepted as normal.

When eye contact is welcome, it evolves into gazing which leads to arousal (See Gazing). Sometimes legitimate liking is present and staring is an indication, but it still remains inappropriate and an assault as it is defined by unwavering and an unwanted violation of privacy. Staring can also indicate boredom or disengagement, but only when it is not directed at a person or target (i.e. staring off into space.)

Cue Cluster: Staring eyes are coupled with expressionless or angry faces. The head usually is fixed unless the target is moving.

Body Language Category: Amplifier, Arrogance or arrogant body language, Aggressive body language, Anger body language, Boredom body language, Disengagement body language, Dislike (nonverbal), Dominant body language, Emotional body language, Indicators of sexual interest (IOsI), Liking, Negative body language, Ownership gestures, Space invasion, Threat displays.

Resources:

Aguinis, Herman ; Simonsen, Melissam. ; Pierce, Charlesa. Effects of Nonverbal Behavior on Perceptions of Power Bases. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1998. 138(4): 455-469.

Aguinis, Herman ; Henle, Christinea. Effects of Nonverbal Behavior on Perceptions of a Female Employee’s Power Bases. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2001 141(4): 537-549.

Argyle, Michael; Lefebvre, Luc; Cook, Mark 1974. The meaning of five patterns of gaze. European Journal of Social Psychology. 4(2): 125-136.

Argyle, M., and Ingham, R. 1972. Gaze, mutual gaze, and proximity. Semiotica, 1, 32–49.

Argyle, M. and Cook, M. Gaze and Mutual Gaze. London: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Allan Mazur; Eugene Rosa; Mark Faupel; Joshua Heller; Russell Leen; Blake Thurman. Physiological Aspects of Communication Via Mutual Gaze. The American Journal of Sociology. 1980; 86(1): 50-74.

Allison, T., Puce, A., & McCarthy, G. (2000). Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends in Cognitive Neurosciences, 4, 267–278.

Breed, G., Christiansen, E., & Larson, D. 1972. Effect of lecturer’s gaze direction upon

teaching effectiveness. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 2: 115.

Bowers, Andrew L. ; Crawcour, Stephen C. ; Saltuklaroglu, Tim ; Kalinowski, Joseph

Gaze aversion to stuttered speech: a pilot study investigating differential visual attention to stuttered and fluent speech. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2010. 45(2): 133-144.

Bond, C. F., Kahler, K. N., & Paolicelli, L. M. (1985). The miscommunication of deception: An adaptive perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 331–345. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(85)90034-4

Burns, J. A., & Kintz, B. L. (1976). Eye contact while lying during an interview. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 7, 87–89.

Beausoleil, Ngaio J. ; Stafford, Kevin J. ; Mellor, David J. Burghardt, Gordon M. (editor). Does Direct Human Eye Contact Function as a Warning Cue for Domestic Sheep (Ovis aries)? Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2006. 120(3): 269-279.

Chen, Yi-Chia ; Yeh, Su-Ling. Look into my eyes and I will see you: Unconscious processing of human gaze. Consciousness and Cognition. 2012 21(4): 1703-1710.

Calogero, Holly M A. Test Of Objectification Theory: The Effect Of The Male Gaze On Appearance Concerns In College Women. Psychology of women quarterly 28.1 (2004) 16-21.

Ellsworth, Phoebe; Carlsmith, J Merrill. 1973. Eye contact and gaze aversion in an aggressive encounter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 28(2): 280-292.

Einav, Shiri ; Hood, Bruce M. García Coll, Cynthia (editor). Tell-Tale Eyes: Children’s Attribution of Gaze Aversion as a Lying Cue. Developmental Psychology. 2008. 44(6): 1655-1667.

Foddy, Margaret 1978. Patterns of Gaze in Cooperative and Competitive Negotiation

Human Relations. 31(11):925-938.

Friesen, C.K., & Kingstone, A. (1998). The eyes have it: Reflexive orienting is triggered by nonpredictive gaze. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 5, 490–493.

George, N., Driver, J., & Dolan, R. J. (2001). Seen gaze-direction modulates fusiform activity and its coupling with other brain areas during face processing. Neuroimage, 13, 1102–1112.

George, N., Driver, J., & Dolan, R. J. (2001). Seen gaze-direction modulates fusiform activity and its coupling with other brain areas during face processing. Neuroimage, 13, 1102–1112.

Goodboy, Alan, K. and Maria Brann. Flirtation Rejection Strategies: Towards an Understanding of Communicative Disinterest in Flirting. The Quantitative Report. 2010. 15(2): 268-278.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/how-to-reject-flirting-using-nonverbal-and-verbal-tactics/

Hietanen, J. K. (1999). Does your gaze direction and head orientation shift my visual attention? Neuroreport, 10, 3443–3447.

Hietanen, Jari. Social attention orienting integrates visual information from head and body orientation. Psychological Research.2002 66(3): 174-179.

Horley K, Williams LM, Gonsalvez C, Gordon E (2003) Social phobics do not see eye to eye: a visual scanpath study of emotional expression processing. J Anxiety Disord 17:33–44

Hemsley, G. D., & Doob, A. N. (1978). The effects of looking behavior on perceptions of a communicator’s credibility. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 8, 136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1978.tb00772.x

Johansson-Stenmen, O. (2008). Who are the trustworthy, we think? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68, 456–465. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2008.08.004

Jenkins, R., Beaver, J.D., & Calder, A.J. (2006). I thought you were looking at me: Direction-specific aftereffects in gaze perception. Psychological Science, 17, 506–513.

Jenkins, R., Keane, J., & Calder, A.J. (2007, August). From your eyes only: Gaze adaptation from averted eyes and averted heads. Paper presented at the Thirtieth European Conference on Visual Perception, Arezzo, Italy.

Kawashima, R., Sugiura, M., Kato, T., Nakamura, A., Hatano, K., Ito, K., Fukuda, H., Kojima, S., & Nakamura, K. (1999). The human amygdala plays an important role in gaze monitoring: A PET study. Brain, 122, 779–783.

Kaminski, Juliane ; Call, Josep ; Tomasello, Michael. Body orientation and face orientation: two factors controlling apes’ begging behavior from humans

Animal Cognition. 2004. 7(4): 216-223.

Kellerman. 1989. Looking and loving: The effects of mutual gaze on feelings of romantic love. Journal of Research in Personality. 23(2): 145-161.

Kendon, A. Some Functions of Gaze Direction in Social Interaction. Acta Psychologica. 1967. 32: 1-25.

Kleinke, C. L. 1980. Interaction between gaze and legitimacy of request on compliance in a field setting. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 5(1): 3-12.

Kampe, K.K.W. ; Frith, C.D. ; Dolan, R.J. ; Frith, U. Direct eye contact with attractive faces activates brain areas associated with ‘reward’ and ‘reward expectation’ Neuroimage. 2001. 13(6): 425-425.

Lance, Brent ; Marsella, Stacy. Glances, glares, and glowering: how should a virtual human express emotion through gaze? Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, 2010. 20(1): 50-69

Leeb. 2004. Here’s Looking at You, Kid! A Longitudinal Study of Perceived Gender Differences in Mutual Gaze Behavior in Young Infants Source: Sex Roles. 50(1-2): 1-14.

Langton, S.R.H. (2000). The mutual influence of gaze and head orientation in the analysis of social attention direction. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology, 53, 825–845.

Langton, S. R. H., & Bruce, V. (1999). Reflexive visual orienting in response to the social attention of others. Visual Cognition, 6, 541–567.

Langton, S. R. H., & Bruce, V. (2000). You must see the point: Automatic processing of cues to the direction of social attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26, 747–757.

Matsuda, Yoshi-Taka ; Okanoya, Kazuo ; Myowa-Yamakoshi, Masako. Shyness in early infancy: approach-avoidance conflicts in temperament and hypersensitivity to eyes during initial gazes to faces. PloS one. 2013 8(6): pp.e65476

Moukheiber A, Rautureau G, Perez-Diaz F, Soussignan R, Dubal S, Jouvent R, Pelissolo A (2010) Gaze avoidance in social phobia: objective e measure and correlates. Behav Res Ther 48:147–151

Montgomery, Derek ; Moran, Christy ; Bach, Leslie. The influence of nonverbal cues associated with looking behavior on young children’s mentalistic attributions.

Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1996. 20(4): 229-249.

McAndrew. 1986. Arousal seeking and the maintenance of mutual gaze in same and mixed sex dyads Source: Journal of nonverbal behavior. 10(3):168-172.

Mccarthy, Anjanie ; Lee, Kang. Children’s Knowledge of Deceptive Gaze Cues and Its Relation to Their Actual Lying Behavior. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009. 103(2): 117-134.

Mann, Samantha ; Ewens, Sarah ; Shaw, Dominic ; Vrij, Aldert ; Leal, Sharon ; Hillman, Jackie. Lying Eyes: Why Liars Seek Deliberate Eye Contact. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2013. 20(3): 452-461.

Mulac, A., Studley, L., Wiemann, J., & Bradac, J. 1987. Male/female gaze in same-sex

and mixed-sex dyads. Human Communication Research. 13: 323-343.

Natale, Michael. 1976. A Markovian model of adult gaze behavior. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 5(1): 53-63.

Puce, Allison, T and McCarthy, G. (2000). Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends in Cognitive Neurosciences, 4, 267–278.

Perrett, D.I., Hietanen, J.K., Oram, M.W., & Benson, P.J. (1992). Organization and functions of cells responsive to faces in the temporal cortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 335, 23–30.

Phelps, F., Doherty-Sneddon, G., & Warnock Educational Psychology., 27, 91-107. (2006). Functional benefits of children’s gaze aversion during questioning. British Journal Developmental Psychology. 24: 577-588.

Ponari, Marta ; Trojano, Luigi ; Grossi, Dario ; Conson, Massimiliano. “Avoiding or approaching eyes”? Introversion/extraversion affects the gaze-cueing effect. Cognitive Processing. 2013. 14(3): 293-299.

Riggio, R. E., & Friedman, H. S. (1983). Individual differences and cues to deception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 899–915. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.899

Rosenfeld, H., Breck, B., Smith, S., & Kehoe, S. 1984. Intimacy-mediators of the proximity-gaze compensation effect: Movement, conversational role, acquaintance, and gender. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 8: 235-249.

Straube, Benjamin ; Green, Antonia ; Jansen, Andreas ; Chatterjee, Anjan ; Kircher, Tilo. Social cues, mentalizing and the neural processing of speech accompanied by gestures. Neuropsychologia. 2010. 48(2): 382-393.

Straube, Thomas ; Langohr, Bernd ; Schmidt, Stephanie ; Mentzel, Hans-Joachim ; Miltner, Wolfgang H.R. Increased amygdala activation to averted versus direct gaze in humans is independent of valence of facial expression. NeuroImage. 2010 49(3): 2680-2686.

Strick, Madelijn ; Holland, Rob W. ; Van Knippenberg, Ad. Seductive Eyes: Attractiveness and Direct Gaze Increase Desire for Associated Objects

Cognition. 2008. 106(3): 1487-1496.

Slessor, Gillian ; Phillips, Louise H. ; Bull, Rebecca ; Venturini, Cristina ; Bonny, Emily J. ; Rokaszewicz, Anna. Investigating the “deceiver stereotype”: do older adults associate averted gaze with deception?(Author abstract). The Journals of Gerontology, Series B. 2012. 67(2): 178(6).

Sporer, S. L., & Schwandt, B. (2007). Moderators of nonverbal indicators of deception: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 13, 1–34. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.13.1.1

Tomasello, M., Hare, B., Lehmann, H., & Call, J. (2007). Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: The cooperative eye hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution, 52, 314–320.

Underwood, M. K.. Glares of Contempt, Eye Rolls of Disgust and Turning Away to Exclude: Non-Verbal Forms of Social Aggression among Girls. Feminism & Psychology. 2004 14(3): 371-375.

Wicker, B., Michel, F., Henaff, M.-A., & Decety, J. (1998). Brain regions involved in the perception of gaze: A PET study. Neuroimage, 8, 221–227.

Williams. 1993. Effects of Mutual Gaze and Touch on Attraction, Mood, and Cardiovascular Reactivity Source: Journal of Research in Personality. 27(2): 170-183.

Weisfeld, Glenn E. and Jody M. Beresford. Erectness of Posture as an Indicator of Dominance or Success in Humans. Motivation and Emotion. 1982. 6(2): 113-130.

http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/body-language-cues-dominance-submission-children/

Wirth, James H ; Sacco, Donald F ; Hugenberg, Kurt ; Williams, Kipling D. Eye gaze as relational evaluation: averted eye gaze leads to feelings of ostracism and relational devaluation. Personality & social psychology bulletin. 2010 36(7): 869-82.

Wang, Yin ; Newport, Roger ; Hamilton, Antonia F De C. Eye contact enhances mimicry of intransitive hand movements. Biology letters. 2011. 7(1): 7-10.

Cue: Sweating or Hyperhidrosis.

Cue: Sweating or Hyperhidrosis.