Body Language of Playing With Objects

Cue: Playing With Objects

Cue: Playing With Objects

Synonym(s): Giggling Change, Opening And Closing Glasses, Running Fingers Over Zippers, Running The Hands Over Stubble, Playing With Keys, Rolling A Ring Around The Finger, Object Play.

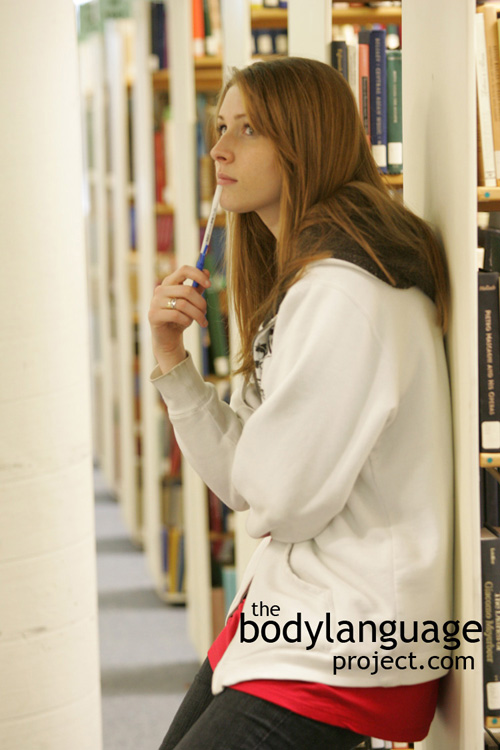

Description: Playing with objects such as a set of keys, ring, change, zippers, or any other artifact that is easy and conveniently located.

In One Sentence: Playing with objects is a way to pacify.

How To Use it: Playing with objects can give others a negative impression of you, however, it does serve a useful purpose. It provides busy hands with an outlet to release emotional tension or placate boredom. A set of keys in a pocket can be manipulated to give the hands something to do while releasing stress relieving hormones through tactile stimulation.

Context: General.

Verbal Translation: “I’m uneasy, insecure, bored, and need to pacify myself by keeping my hands busy.”

Variant: See Masked Arm Cross, Fondling A Cylindrical Object, Covering The Neck Dimple or Hand to Lower Neck.

Cue In Action: a) The widower played with his wristwatch. It provided him a sense of comfort during stressful events. b) While waiting for the bus, he rolled his ring around his finger due to sheer boredom. c) When she couldn’t think of the answer on the test she twisted the eraser back and forth trying to squeeze the answer out of her mind. d) She always felt awkward on the subway and made a habit of placing her handbag on her lap. When someone she didn’t approve of sat near her, she opened her purse and sorted through her belongings to displace her negative feelings.

Meaning and/or Motivation: Playing with objects is a sign that the body needs to be pacified and is suffering from inner turmoil and discomfort or outright boredom. Most are rooted in infantile actions such as playing with a favourite toy, hugging a blanket, sucking a soother and being comforted by mom or dad. The object keeps the hands busy and helps pacify by burning up some of the excess negative energy. Playing with objects creates a soothing touch over the fingers or palms helping to release positive hormones further reinforcing the behaviour.

If the object belongs to another person, it might signal the desire to be with them and in effort to reestablish closeness. If a loved one has passed away, they may stroke a necklace given to them by this person. This too is a signal that insecurity is taking place and they are seeking their affiliation to the person for support.

Many different forms of object play exist. A person might jiggle change in their pocket, play with a pen or jewelry, open and close the arms of glasses, adjust clothing, shaking a shoe, smoking, or running fingers through the hair.

Cue Cluster: The context, more so than other cues will decide the true meaning of playing with objects.

Body Language Category: Boredom body language, Displacement behaviour, Pacifying body language, Security blankets, Stressful body language.

Resources:

Argo, J. J., Dahl, D. W., & Morales, A. C. (2006). Consumer contamination: How consumers react to products touched by others. Journal of Marketing, 70(April), 81–94.

Almerigogna, Jehanne; James Ost; Lucy Akehurst and Mike Fluck. How Interviewers’ Nonverbal Behaviors Can Affect Children’s Perceptions And Suggestibility. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2008. 100:17-39.

How To Get Children To Tell The Truth Using Body Language

Argo, J. J., Dahl, D. W., & Morales, A. C. (2006). Consumer contamination: How consumers react to products touched by others. Journal of Marketing, 70(April), 81–94.

Farley, James; Risko, Evan F; Kingstone, Alan. Everyday Attention And Lecture Retention: The Effects Of Time, Fidgeting, And Mind Wandering. Frontiers In Psychology, 2013; 4: 619

Mind Wandering, Fidgeting And Attention

Berridge CW,Mitton E, ClarkW, Roth RH. 1999. Engagement in a non-escape (displacement) behavior elicits a selective and lateralized suppression of frontal cortical dopaminergic utilization in stress. Synapse 32:187–197.

Boniface, D., & Graham, P. (1978). The three-year-old and his attachment to a special soft object. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20, 217–224.

Cardasis, W ; Hochman, J A ; Silk, K R. Transitional objects and borderline personality disorder. The American journal of psychiatry 1997, Vol.154(2), pp.250-5.

Cohen, Keith N. ; Clark, James A. Hogan, Robert (editor). Transitional object attachments in early childhood and personality characteristics in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984. 46(1): 106-111.

Claus, B., & Warlop, L. (2010). Once bitten, twice shy: Attitudes towards humans spill over to anthropomorphizable products. Jacksonville, FL: Association for Consumer Research.

Chandler, J., & Schwarz, N. (2010). Use does not wear ragged the fabric of friendship: Thinking of objects as alive makes people less willing to replace them. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20, 138–145.

Claus, B., & Warlop, L. (2010). Once bitten, twice shy: Attitudes towards humans spill over to anthropomorphizable products. Jacksonville, FL: Association for Consumer Research.

Donate-Bartfield, E., & Passman, R.H. (2004). Relations between children’s attachments to their mothers and to security blankets. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(3), 453–458.

Erkolahti, R., & Nystro¨m, M. (2009). The prevalence of transitional object use in adolescence: is there a connection between the existence of a transitional object and depressive symptoms? European Child Adolescence Psychiatry, 18, 400–406.

Everly, Jr., G. S. & Lating, J. M. (2002). A clinical guide to the treatment of the human stress response (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114, 864–886.

Feldman, R., Singer, M.,& Zagoory, O. (2010). Touch attenuates infants’ physiological reactivity to stress. Developmental Science, 13(2), 271–278.

Gregersen, Tammy S. Nonverbal Cues: Clues to the Detection of Foreign Language Anxiety. Foreign Language Annals. 2005. 38(3): 388-400

What Anxious Learners Can Tell Us About Anxious Body Language– How To Read Nonverbal Behavior

Garnefski N 2004) Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: differences between males and female. Personal Indiv Diff 36: 267–76.

Hall, Jeffrey A. and Chong Xing. The Verbal and Nonverbal Correlates of the Five Flirting Styles. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2015. 39:41–68. DOI 10.1007/s10919-014-0199-8

The First 12 Minutes Of Flirting Using Nonverbal Communication – Study Reveals 26 Body Language Cues Of Attraction

Hadi, R., and Valenzuela, A., A meaningful embrace: Contingent effects of embodied cues of affection. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2014. http://bodylanguageproject.com/articles/whats-in-a-nonverbal-object-caress/

Hobara, M. (2003). Prevalence of transitional objects in young children in Tokyo and New York. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24, 174–191.

Kalpidou, M., & Gilson, C. (2010). Sensory processing and children’s attachment to comfort objects. Poster session presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for Psychological Science, Boston, MA.

Kalpidou, Maria. Sensory Processing Relates to Attachment to Childhood Comfort Objects of College Students. Early Child Development and Care. 2012. 182(12): 1563-1574.

Krishna, A., & Morrin, M. (2008). Does touch affect taste? The perceptual transfer of product container haptic cues. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(6), 807–818.

Katza, Carmit; Irit Hershkowitz; Lindsay C. Malloya; Michael E. Lamba; Armita Atabakia and Sabine Spindlera. Non-Verbal Behavior of Children Who Disclose or do not Disclose Child Abuse in Investigative Interviews. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012. 36: 12-20.

Reading Nonverbal Behaviour In Child Abuse Cases – How To Encourage Children To Divulge Information In Truth Telling

Lastovicka, J. L., & Sirianni, N. J. (2011). Truly, madly, deeply: Consumers in the throes of material possession love. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(2), 323–341.

Leanne ten Brinke; Dayna Stimson and Dana R. Carney. Some Evidence For Unconscious Lie Detection. Published online before print March 21, 2014, doi: 10.1177/0956797614524421.

To Spot A Liar Trust Your Gut Not Your Eyes

Lehman, E.B., Arnold, B.E., & Reeves, S.L. (1995). Attachments to blankets, teddy bears, and other nonsocial objects: A child’s perspective. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 156(4), 443–459.

Lehman, E.B., Arnold, B.E., Reeves, S.L., & Steir, A. (1996). Maternal beliefs about children’s attachments to soft objects. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66(3), 427–436.

Lehman, E.B., Denham, S., Moser, M.H., & Reeves, S.L. (1992). Soft object and pacifier attachments in young children: The role of security of attachment to the mother. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33(7), 1205–1215.

Lehman, E.B., Holtz, B.A., & Aikey, K.L. (1995). Temperament and self-soothing behaviour in children: Object attachment, thumbsucking, and pacifier use. Early Education and Development, 6(1), 53–72.

Liss, M., Timmel, L., Baxley, K., & Killingsworth, P. (2005). Sensory processing and its

relation to parental bonding, anxiety, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1429–1439.

Meier, B. P., Schnall, S., Schwarz, N., & Bargh, J. A. (2012). Embodiment in social psychology. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 705–716.

Mahalski, P. (1983). The incidence of attachment objects and oral habits at bedtime in two longitudinal samples of children aged 1.5–7 years. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 24(2), 283–295.

Mahalski, P.A., Silva, P., & Spears, G. (1985). Children’s attachment to soft objects at bedtime, child rearing, and child development. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24(4), 442–446.

Mack, Avram H. ; Viederman, Milton. The Use of a Transitional Object in the Context of Medical Illness. Psychosomatics. 2000. 41(5): 433-435.

Moore, Monica. Courtship Signaling and Adolescents: Girls Just Wanna Have Fun. Journal of Sex Research. 1995. 32(4): 319-328.

Girls Just Want To Have Fun – The Origins Of Courtship Cues In Girls And Women

Moore, M. M. and D. L. Butler. 1989. Predictive aspects of nonverbal courtship behavior in women. Semiotica 76(3/4): 205-215.

Moore, M. M. 1985. Nonverbal courtship patterns in women: context and consequences. Ethology and Sociobiology 64: 237-247.

Maestripieri D, Schino G, Aureli F, Troisi A. 1992. A modest proposal: displacement activities as an indicator of emotions in primates. Anim Behav 44:967–979.

Mohiyeddini, C., Bauer, S., & Semple, S. (2013a). Displacement behaviour is associated with reduced stress levels among men but not women. PLoS One, 8, e56355.

Mohiyeddini, C., Bauer, S., & Semple, S. (2013b). Public self-consciousness moderates the link between displacement behaviour and experience of stress in women. Stress, 16, 384–392.

Mohiyeddini, C., & Semple, S. (2013). Displacement behaviour regulates the experience of stress in men. Stress, 16, 163–171.

Peck, J., & Shu, S. B. (2009). The effect of mere touch on perceived ownership. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(Oct), 434–447.

Pecora, Giulia ; Addessi, Elsa ; Schino, Gabriele ; Bellagamba, Francesca. Do displacement activities help preschool children to inhibit a forbidden action? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2014. 126: 80-90.

Peck, J., & Wiggins, J. (2006). It just feels good: Consumers’ affective response to touch and its influence on persuasion. Journal of Marketing, 70(Oct), 56–69.

Passman, R.H. (1987). Attachments to inanimate objects: Are children who have security blankets insecure? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(6), 825–830.

Passman, R.H., & Halonen (1979). A developmental survey of young children’s attachments to inanimate objects. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 134, 165–178.

Steir, A., & Lehman, E.B. (2000). Attachment to transitional objects: Role of maternal personality and mother-toddler interaction. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(3), 340–350.

Sturman, Edward D. Invluntary Subordination and Its Relation to Personality, Mood,

and Submissive Behavior. Psychological Assessment. 2011. 23(1): 262-276 DOI: 10.1037/a0021499

Nonverbal Submission In Men And Women In Depression – A Critical Examination Of The Use And Disuse Of Submission

Schino G, Perretta G, Taglioni AM, Monaco V, Troisi A. 1996. Primate displacement activities as an ethopharmacological model of anxiety. Anxiety 2:186–191.

Sigall, H., & Johnson, M. (2006). The relationship between facial contact with a pillow and mood. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 505–526.

Seli, Paul; Jonathan S. A. Carriere; David R. Thomson; James Allan Cheyne, Kaylena A. Ehgoetz Martens, and Daniel Smilek. Restless Mind, Restless Body Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. American Psychological Association. 2014. 40(3): 660-668. DOI: 10.1037/a0035260

What Does Fidgeting Body Language Really Mean? Do We Fidget When We’re Bored Or Mentally Taxed?

Triplett, June L. ; Arneson, Sara W. The Use of Verbal and Tactile Comfort to Alleviate Distress in Young Hospitalized Children. Research in Nursing & Health. 1979. 2(1): 17-23.

Tamres L, Janicki D, Helgeson VS (2002) Sex differences in coping behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 6: 2–30.

Troisi A (2002) Displacement activities as a behavioural measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress 5: 47–54.

Troisi A (1999) Ethological research in clinical psychiatry: the study of nonverbal behaviour during interviews. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 23: 905–913.

Troisi A, Moles A (1999) Gender differences in depression: an ethological study of nonverbal behaviour during interviews. J Psychiatr Res 33: 243–250.

Van Der Zee, Sophie; Ronald Poppe; Paul J. Taylor; and Ross Anderson. To Freeze or Not to Freeze A Motion-Capture Approach to Detecting Deceit.

Detect Lies With Whole Body Nonverbals – New Lie Detector Successful Using Body Language At Over 70%

Williams, L. E., Huang, J. Y., & Bargh, J. A. (2009). The scaffolded mind: Higher mental processes are grounded in early experience of the physical world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 1257–1267.

Winnicott, D.W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 34, 89–97.