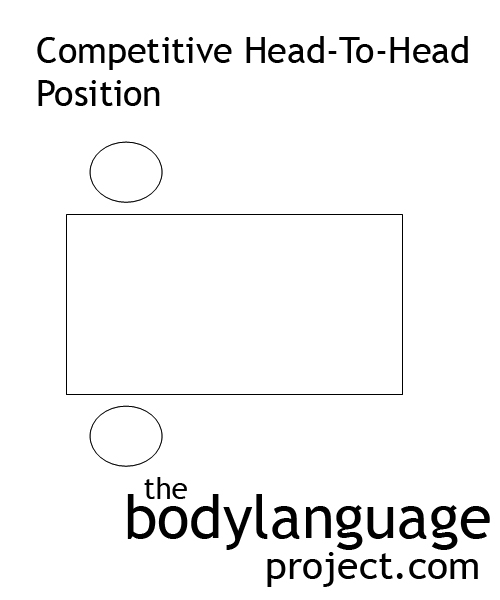

Legal television dramas popularize this head-to-head seating position. Here each party faces directly across from the other person usually with their allies to their left and right solidifying their flanks. Another words for this position is the “closed” seating arrangement because it isolates people with the use of the desk. In the “open” arrangement a desk is pushed up against a wall and presents no barrier to visitors since they can access every part of a person when meeting with them. Closed positions convey formality, distance and authority, defensiveness and even divisiveness whereas open orientations convey interest and comfort.

Even when competition isn’t directly encouraged, research finds that the closed position still becomes an issue because the table provides a clear boundary between each party. Despite this, studies show that it is a very common way to sit in for casual conversations and at restaurants. The reason expressed is because it easily permits the exchange of information, affords good eye contact by filling the other persons view, and turns each person into the centre of attention. Thus, while it can be a constructive casual position amongst friends and family, it doesn’t serve well with new associates or where there is a desire to break down existing boundaries.

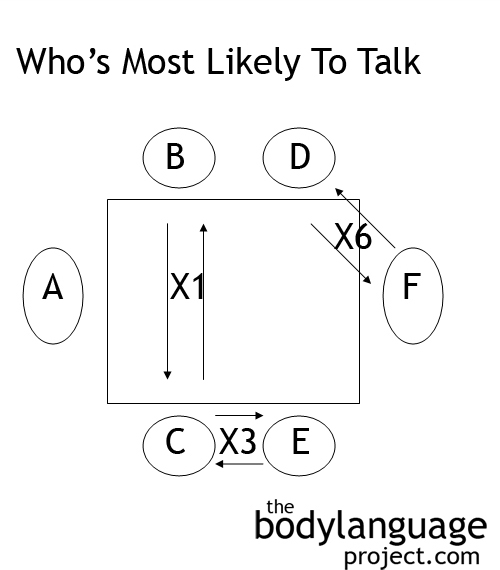

Interestingly when larger groups meet in the competitive arrangement with many people facing one another across a rectangular table, it is most often the person to the front of the speaker directly across the table that talks next, and rarely the person to their side. This has been termed the “Steinzor effect” and was named after the researcher Dr. Bernard Steinzor in 1950 who first discovered the occurrence. The head-to-head position creates discourse and necessitates the person at their face to respond, moreso than any other at the table. This only adds to the negative data that stem from head-to-head orientations and why we should avoid it when we wish to accomplish something other than fight.

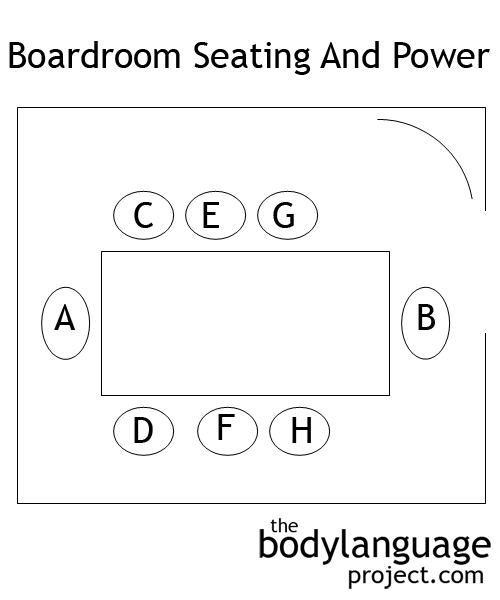

Research conducted in the mid 1970’s by psychologist Richard Zweigenhaft of Guildord College in North Carolina found that faculty that used their office desks as a barrier by placing it in between them and their students were rated less positively in general and where rated especially poorly as it related to student interaction. The study found that faculty that did this were also older and had a greater academic rank. Thus, it was likely their subconscious tendency was to protect and maintain their rank between themselves and their students. Therefore, when meeting with new clients or where competition is likely but undesirable, avoid sitting in the head-to-head position if possible and remove whatever barriers separate you and whomever it is you wish to build a relationship with. However, if the desire is to reprimand an employee or anyone else and the goal to set clear boundaries, the table-in-between-position can emphasis division, thereby enhancing the message further. It will be up to you to decide exactly what orientation will suite you best and this will be wholly dependant on the goal you wish to attain while meeting.