In this chapter we looked in depth about space or territory and how it influences body language. We learned that the term applied to how people use space is proxemics and it includes personal space, distance norms, how cultures and regionality such as rural and urban centers are reflected in personal space, and how they relate to status and context. We learned why people turn into zombies in crowded city streets, how eye contact can control intimacy and why we should respect people’s personal space comforts no matter where they hail. We then played the urinal game and showed how space ties together with this ritual, and finally we covered indicators of invasion which can help us in respecting space limitations when in novel situations, or when around new acquaintances.

Chapter 4 – Space and Territory

Indicators of Invasion

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

There are some very simple ways in which people indicate that they are being invaded, and they are important should one want to avoid offending them. As we have learned in this chapter, personal space is important to all people and so we want to be cautious not to intrude on others for two reasons: first, for the sake of the comfort of the people around us, and second, for our own sake, so that people don’t attach negative ideas to us.

Strangers should be given the most amount of space until we get to know them so we should avoid breaking the five foot separation mark unless invited to do so. While it might seem rude to keep a new acquaintance at a distance and five feet might even seem like a huge distance, it’s a clearly defined ritual and a benchmark that most people find commonplace. For those that use touch to display connectivity (the touchy-feely ones) should show reservation at least until proper rapport is built and your acquaintance shows relaxed and open signals. Handshakes are common across most culture and are acceptable greeting method when meeting new people. The kiss-hello and other more intimate methods to greet find their place in many cultures, but the handshake is becoming more and more popular across the globe, so it’s a fairly safe bet it will be well received. After the handshake is complete, on should take a step back or to the side to converse. Next, you should allow the other person to define their preferred zone in which to carry on the remainder of the interaction. This is done by allowing them to move forward or backward if they desire. Eventually you will find a happy medium between you and them, so do avoid continuously approaching or leaning forward, in other words, plant your feet and keep an upright body.

Your partner will signal that you are encroaching on them and making them feel uncomfortable by taking a step backwards. If this isn’t possible due to space restrictions, or while in tight quarters such as an elevator, or if continuously followed by advancements, your partner will begin to pull their heads backwards and away. Even when space is not limited, we may find that polite people that don’t wish to overtly show that they are being infringed upon may also simply pull their heads back versus stepping backwards. If you find that you are constantly moving forward, then it’s likely because your comfort distance is less than the comfort distance of others.

Others might just show a bigger smile (possibly showing stress) and simply pretend that nothing is bothering them, but as soon as eye contact is broken or when their speaking partner is distracted, will take a step back. Others still, can pull their arms up and out to reserve space or can use their hand on the sleeve of the other to keep them from advancing. Arm crossing also demonstrates a negative posture and is used to shield the body so this can also indicate encroachment. Respecting other people’s intimate zones is extremely important. Invading people’s space can cause anxiety, irritation, anger or fear. If all else fails, you know you’ve exceeded the general personal space of others when your eyes begin to fuzz or cross, or you feel the uncomfortable sensation of warm breath on your face. When all else fails, take a step back and let them close the gap.

The Urinal Game

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

The urinal game is a thought experiment designed to illustrate what territory and space mean in today’s modern world. Sure it involves a little bathroom humour, but if you bear with it, so to speak, you’ll be relieved. The goal of the game is to decide on which urinal is the most appropriate to use given the set of variables. In the game, there are six upright urinals to choose from, and they are ordered from the entry or doorway, to the end of the washroom. Urinal 1 is closest to the door and urinal 6 is closest to the end wall. The ideal urinal, of course, is the one that protects your privacy the most. Specifically it is the urinal that maximizes the amount of space between you, and the next person. The urinal game is not much different than what everyone does daily as we navigate crowded areas or chose seating in busy cafeterias.

1. All 6 urinals are empty. Which do you choose?

2. Now urinal 2 and urinal 4 are occupied. Which is the proper urinal?

3. Urinal 2, 4 and 6 are all occupied. Which is the proper urinal?

4. Urinal 1, 2, 5 and 6 are now all occupied.

Answers: 1) While urinal 1 and 6 are both acceptable answers the most correct answers is urinal 6 since it prevents anyone needing to pass in behind you while you urinate. Both urinal 1 and 6 are somewhat correct since the end wall prevents being flanked on either side. 2) Urinal 6 is the answer once again for similar reasons as in the first scenario. 3) This one is a catch since you are bound to be stuck next to at least one other guy. However, option 1 is the best since it affords at least some space between you and the others instead of being right up against another guy. 4) This answer is simple. You don’t use any of the urinals! Instead, you go to the mirror or pre-wash your hands, fix your hair, adjust your tie or suck up your pride and use a stall!

Some additional rules to this urinal game which are similar to the games we play in elevators include: Absolutely no touching permitted other then yourself. No talking or singing unless you are with close buddies or are heavily intoxicated, and even then, it should be kept to a minimum especially while urinating. Glances are a one time affair and are simply used to acknowledge the presence of others and nothing more.

Throw them a curve at the urinals! In rather bizarre experiment, researchers measured the time taken to micturate (to you and me, this means to pee) either with or without someone standing directly next to them. Not surprisingly, closer distances led to increases in micturation delay and a decrease in micturation persistence! With this ground breaking research we can conclude two things: 1) Peeing is harder to do around strangers because it prevents us from relaxing our external urethral sphincter and shortens peeing because it increases intravesical pressure once begun; and on a slightly more serious and applicable note 2) Stranger who invade our personal space increases our arousal and anxiety preventing us from getting relatively even unimportant things done. Imagine how space invasion affects more important tasks!

Spatial Empathy

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

“Spatial empathy” is an informal term used by expatriate workers in Hong Kong and then later in Japan and China who were typically from Australia, England, France and the United States. The term was use to describe the awareness that individuals have about how their proximity affects the comfort of the people around them. Even though cities such as Hong Kong, Japan and China were westernized, the walkways and public transport system were very crowded by comparison. The expatriates found that preventing intrusion into their personal space was difficult and at times impossible.

The foreign workers that were not accustomed to physical closeness and physical contact were made to feel violated by the locals. They felt that their privacy was being infringed upon and that their personal space requirements weren’t being met. What the workers failed to realize was that it was their responsibility to adapt to the cultural norms of the locals and not the other way around so while the locals had no spatial empathy the workers had no cultural empathy.

While spatial empathy was first coined to describe the differences between cultures it also has application within cultures as some people have different levels of tolerance with regards to their personal space. Naturally, it is your choice to decide what you will do with someone else’s preference, be it to respect it by reading their signals and give them space, or ignore it and invade it. I supposed it would have everything to do with what your goals happens to be. Will you respect the needs of the people around you and try to make them feel comfortable or will you invade their space to fulfill your own needs?

Space And Eye Contact

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

You can imagine that strangers walking about in public want to maintain a certain degree of separation between one another. This can and is achieved through eye contact. Reducing or preventing eye contact is a way to tell other people that they wish to maintain their space and privacy, and do not wish to communicate with others. Eye contact is a function of intimacy and has been referred to as part of the equilibrium state. That is, eye contact is one component that controls the degree of intimacy, the other is distance. By controlling one or the other, or both, we can control aspects of our equilibrium state, or intimacy, such as whether it will start at all, and how or when it should end. You can imagine that full intimacy can not happen at great distances although telephones and web technology attempt to do otherwise. Each fails miserably and does intimacy no justice.

As distance increases, intimacy decreases so you can imagine that strangers would feel freer to glare at others from say, across the road, but as they near the point at which they intersect they will drop or avert their eyes so as to eliminate intimacy. Therefore, that which gives permission for staring is distance and that which protects intimacy is eye contact. To have real intimacy both proximity and eye contact must be present. By this argument, city people aren’t rude at all, they are just doing what is normal, avoiding unwanted intimacy from strangers. Rural settings where there is a real possibility that you actually know the person on the street, or know a relative of the person is large, so intimacy is not only permitted by also safe. Eye contact in the city can send the wrong message to the wrong person inviting unwanted contact.

To illustrate this point imagine a women who is happily married but otherwise attractive to men. Upon entering a coffee shop, she turns the heads of men. When she notices that she is being watched, she averts her gaze and instead of making eye contact she ‘looks over the heads of others’ or possibly even looking down her nose at them by tilting her head backward showing disapproval. She sends a disinterested message, an “I’m taken.” If startled, she might inadvertently make eye contact with a stranger but she will instinctively drop her head and avert her gaze sideways, being careful to make no emotion facial expressions. In doing so, she avoids emitting the wrong message and therefore prevents unwanted solicitation. Men are often victims of assuming any eye contact is flirtatious, even if it happens by accident, thus women are generally careful of whom they look at directly. Some women learn this through a bad experience; others seem to know it instinctively. Men can test this out for themselves by trying to secure eye contact with women as they pass them on the street. Men are rarely able to secure eye contact from strangers and it’s usually not for a lack of trying.

People As Objects

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

This is why city streets are flooded with strangers behaving like zombies with expressionless faces as they hurry about. City folk seem inhuman and unemotional, detached, despondent and more than anything else, from an outsider’s perspective, they appear unhappy. Contrast this with a small city where eye contact is met with smiles, nods or waves and where doors are held open for others with words such as “thank you” provided in exchange.

So why do busily moving city slickers seem as though they are moving about a forest of trees, instead of a sea of actual living human beings with emotions and feelings? Why do city slickers dehumanize themselves? The answer lies in phenomenon termed “masking.” Masking is a coping strategy used to detach ourselves from our bodies so as to avoid negative feelings as we intrude on the personal space of others and as our personal space is intruded upon. Sometimes we even mask with outwardly aggressive emotions typified by New York streets. Cussing, yelling and other carrying on is a way to mask sensitivity and to hide caring. This is not to say that one becomes less human in New York, it just means that you can’t appear to be a wimp.

Masking helps people protect themselves from their emotions and is so potent that it is difficult sometimes to snap people from this hypnosis. Sometimes even making eye contact with others can be seen as offensive and returned only with an expressionless face, a glare, or even a snarl as if implying that the issue is that of another and not theirs.

Just like country folk expect and appreciate amicable greetings, smiles, waves and nods, city slickers expect and appreciate emotionless faces, few or no greetings and for people to mind their own business. Don’t confuse either situation for anything other than a coping mechanism. Taken in similar context, you might just see how similar each breed of people really is.

Here is a breakdown of ways we act in crowded places like subways and elevators:

[A] We stand or sit still, unmoving. The more crowded the area, the more frozen we remain.

[B] The face becomes blank and expressionless, but it is not due to negative thoughts but rather as a coping mechanism.

[C] Eye contact is avoided by looking at the floor or ceiling.

[D] Books, newspapers and other devices appear particularly interesting and immersive, serving to detach the self emotionally from the situation.

[E] Under extremely crowded conditions where touching is unavoidable, bodies appear to jostle to make space and if possible only allow shoulders and elbows to touch.

Status, Context And Personal Space

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

Status and context affect spatial and proximity rules. For example, bosses are in charge of determining what level of closeness is appropriate and permitted as it relates to subordinate employees. This isn’t to say that employees enjoy this arrangement but rather that employees are not permitted to reverse proximity rules onto employers. Subordinate employees have many roles and one of them is tolerance of the rules set for them by their seniors. For example, a boss might pat the back of one his employees or put his or her arm around the new associate as a form of bonding. Reversal of the situation would be seen as an infringement on the status of the boss. When it comes to touching, a subordinate should never encroach on the personal space of someone holding a dominant position.

Contextual rules also exist with respect to personal space. In the office, it would be un-acceptable for sexual partners to touch one another or carry on in front of others. However, in the same office hosting a year-end business party with all of the same employees and their spouse’s, touching and even kissing would be common place.

Therefore, status and context are two other factors we should be conscious of as they relate to proximity and space.

Personal Space And Country Folk

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

As mentioned, city people require less space than those living in more rural settings. It’s easy to tell if someone is from the city or country by how they choose to greet each other. Waving is commonplace in the country because it can be done at great distance. Neighbours, or passers-by separated by several hundred yards, or more, cannot afford to extend hands for a handshake, nor do they require it. A simple wave of the hand in the country is sufficient and even welcomed. Unbeknownst to the city slicker, a handshake may even raise suspicion or contempt in a rural setting creating all sorts of bad feelings.

Outsiders can often be seen as intruders, as seeming to be selling something or wanting something or up to no good. Those living in the country infrequently come in contact with people they don’t know forcing their personal space zones even larger, by as much as three or more feet.

When approaching someone who resides in rural settings, and where a handshake is welcomed, it is customary to extend your hand forward by bending at the waste and keeping your feet planted. Extending your hand, but keeping your body as far away as possible shows that you respect their need for space. How far forward someone prefers to extend their hand is an indicator of their space requirements. People from the city will often walk forward in attempt to shrink the distance between their acquaintances and in turn end up bending their elbows as they shake. The opposite is found in country folk who will keep their arms straight out to maintain distance. Those that shake hands by thrusting forward are also indicating their need to maintain a larger space buffer. This preference for space provides a useful bit of information which should be noted.

Culture And Personal Space

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

Personal needs for space are largely based on environment and culture. For example, those in Latin and Japanese cultures require less space than say Nordic cultures and this is based simply on the raw density in which the people reside. Personal spaces needs are therefore not inherent, but are instead cultural and learned. Cultures that require more space than average include Australians and Mongolians whom are the least densely populated independent country of the world. Cultures that require less space include: Italians, Japanese and Indians since the generally inhabit greatly populated countries. More to this, is the fact that those who grew up in more rural settings such as farmers require even more space than those who grew up in cities.

Here is a breakdown of cultural norms by region:

[A] North Americans and West Europeans. Talk at a distance where outstretched arms might touch at their fingertips.

[B] Russians. Talk at a distance whereby the wrists of outstretched arms touch.

[C] Latin Americans, Italians and Arabs. Talk at a distance where the elbow could touch the body of the other.

Just by knowing that these differences occur affords us a greater understanding and tolerance of other people across cultures which can allow us to treat guests appropriately or give us hints about what we can expect from our host country when traveling. Another factor that controls personal space preferences are environment in nature. Crowded pubs or malls, or even elevators, produce a different set of expectations in all people despite their cultural preferences. Even rural inhabitants know that a full five foot buffer, or greater, is not always possible. Gender also plays a role where females generally prefer a larger buffer between themselves and strangers especially when that stranger is male and conversely tolerate and sometimes even appreciate smaller buffers between close female friends. Some trains for example are specially designated to only carry female passengers to prevent men from enter their personal space especially by men. This luxury guarantees women the safety and privacy routinely enjoyed by men. Men, on the other hand, will generally stand further away from other men then the norm, and permit women to stand closer.

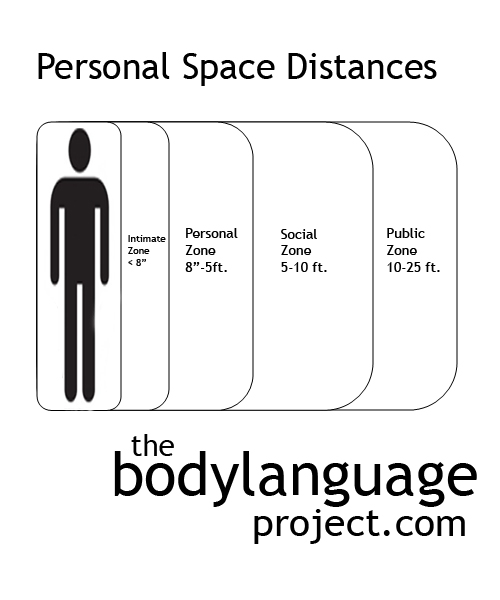

Personal Space Distances

by Chris Site Author • March 5, 2013 • 0 Comments

There are four distances by which people interact. They are the “intimate distance” where only about eight inches or less separates two people, the “personal distance” from eighteen inches to five feet, the “social distance” which is from five to ten feet and the “public distance” which is from ten feet to twenty-five feet. We tolerate intimate distances for embracing, touching, or whispering from sexual partners, family members and occasionally, even friends. Personal space is reserved for good friends and those we have a fairly high level of trust. The social distance is reserved for acquaintances that we perhaps don’t fully trust yet, but otherwise need to interact with, and the public distance is that which we use to address large audiences.

An arm is extended to indicate that personal space is being violated and protect a personal space bubble.

Our personal space, the area next to our bodies, which we protect against intrusion, has been referred to as a “bubble”, since it encircles us, but it more closely resembles a cylinder. The cylinder encompasses our entire bodies, from our feet to our head. It is this cylinder that we protect rigorously, and when it is violated we tense up or back away so as to reduce or prevent additional overlap from the cylinders of others. Our personal space isn’t totally fixed either. It is constantly expanding and contracting depending on our environment and company. For example, we permit children, pets, and inanimate objects into our personal space regularly because we do not perceive them as a threat, but other adults must earn our trust before entering. Our personal space tolerances are directly related to the strength of our relationship.

In basic terms, our personal space zone is the perimeter that we feel is suitable to act as a buffer should a dangerous situation arise. It provides us with enough time and space, we think, to react and mount a defensive posture to protect ourselves from an attack. In a busy public area, we might tolerate (although not prefer) moderate contact due to space limitations, but when space is abundant we see even mild intrusions as a predictors of an attack. Our personal space zone, therefore, is an early warning system that we use to help us predict the intensions of others.

These zones and distances are not immutable and universal, but are meant as a guide or rule of thumb. Everyone has different levels of comfort based upon their upbringing, personality type, gender, age and so forth. The summary listed below is a guideline that is meant for those living in areas such as Australia, Canada, United States, Great Britain and New Zealand or other westernized countries such as Iceland and Singapore or Guam. For other countries not listed, the zones may expand or contract based on the inverse of their density. For example, Japan and China which have a high density have smaller intimate zone distances. There is an inverse correlation to each zone, where the greater the population density, the tighter the zones.

The safest way to test a person’s need for personal space is to move close, lean in, give a hearty but not overly aggressive handshake, then take a step back to allow the person to either move in closer to shrink the space between you and them or take a step backward, to suite a larger than average personal space requirements. Too often people will move in too tight and overshadow someone else only to make them uncomfortable. If someone requires less space, they won’t feel offended to take up the space between you, and if you care anything about them, you won’t feel a need to step backwards either. Shrinking space is a way for people to tell you that they enjoy you, and your company, and one that you should not take offense to, but rather use as a measure of someone’s level of comfort.

1. Intimate zone – eight inches and less. This is our intimate space which we protect vigorously. We permit only those we trust emotionally to enter including parents, children, friends, lovers, relatives and pets. Lovers (and pets) are the only ones we permit to enter for any length of time, the rest we allow entry for only short instances such as for hugs.

2. Personal zone – eight inches to five feet. This is the distance from which we communicate to acquaintances; those we have achieved some level of trust. Examples include bosses and fellow employees, friends of friends, and so forth.

3. Social zone – five feet to ten feet. Normal for people on a first encounter such as people on the street asking for directions, a clerk at a store, strangers at a supermarket and other people we don’t know very well. Here we struggle between conflicting needs, one is to maintain enough space for comfort and the other is to be close enough to communicate effectively.

4. Public zone – ten feet to twenty-five feet. This is the zone at which it is comfortable to address a large group of people or audience during a presentation or speech. Even if we know all the members of the group well, we still maintain a greater distance from them so we can easily address all of them and keep everyone in our field of view. This could be an evolutionary adaptation since a large group could easily contain rogue defectors. By getting too close to an audience we risk surprise attack which is why we feel more comfortable with a wider buffer. Then again, it could simply be a function of judging the efficacy of our speech by measuring the audience’s reaction.