The urinal game is a thought experiment designed to illustrate what territory and space mean in today’s modern world. Sure it involves a little bathroom humour, but if you bear with it, so to speak, you’ll be relieved. The goal of the game is to decide on which urinal is the most appropriate to use given the set of variables. In the game, there are six upright urinals to choose from, and they are ordered from the entry or doorway, to the end of the washroom. Urinal 1 is closest to the door and urinal 6 is closest to the end wall. The ideal urinal, of course, is the one that protects your privacy the most. Specifically it is the urinal that maximizes the amount of space between you, and the next person. The urinal game is not much different than what everyone does daily as we navigate crowded areas or chose seating in busy cafeterias.

1. All 6 urinals are empty. Which do you choose?

2. Now urinal 2 and urinal 4 are occupied. Which is the proper urinal?

3. Urinal 2, 4 and 6 are all occupied. Which is the proper urinal?

4. Urinal 1, 2, 5 and 6 are now all occupied.

Answers: 1) While urinal 1 and 6 are both acceptable answers the most correct answers is urinal 6 since it prevents anyone needing to pass in behind you while you urinate. Both urinal 1 and 6 are somewhat correct since the end wall prevents being flanked on either side. 2) Urinal 6 is the answer once again for similar reasons as in the first scenario. 3) This one is a catch since you are bound to be stuck next to at least one other guy. However, option 1 is the best since it affords at least some space between you and the others instead of being right up against another guy. 4) This answer is simple. You don’t use any of the urinals! Instead, you go to the mirror or pre-wash your hands, fix your hair, adjust your tie or suck up your pride and use a stall!

Some additional rules to this urinal game which are similar to the games we play in elevators include: Absolutely no touching permitted other then yourself. No talking or singing unless you are with close buddies or are heavily intoxicated, and even then, it should be kept to a minimum especially while urinating. Glances are a one time affair and are simply used to acknowledge the presence of others and nothing more.

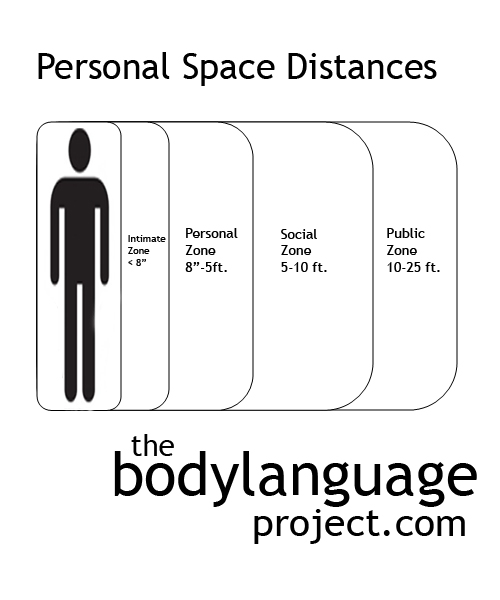

Throw them a curve at the urinals! In rather bizarre experiment, researchers measured the time taken to micturate (to you and me, this means to pee) either with or without someone standing directly next to them. Not surprisingly, closer distances led to increases in micturation delay and a decrease in micturation persistence! With this ground breaking research we can conclude two things: 1) Peeing is harder to do around strangers because it prevents us from relaxing our external urethral sphincter and shortens peeing because it increases intravesical pressure once begun; and on a slightly more serious and applicable note 2) Stranger who invade our personal space increases our arousal and anxiety preventing us from getting relatively even unimportant things done. Imagine how space invasion affects more important tasks!